Scott Farrar is among the most important visual effects supervisors of American cinema. He has been nominated for an Academy Award six times, winning once for Cocoon (1985) directed by Ron Howard. In its incredible filmography, films such as Star Trek: The motion picture, Back to the Future trilogy, Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Jurassic Park, Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace, Deep Impact, A.I. Artificial Intelligence, Minority Report, The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and the Transformers film series. He is a member of VES, ASC, DGA, AMPAS.

What were your studies?

I was a student in the UCLA Film Department. I had no relatives in the business, so it was a big gamble to figure out how to get work in the film world. UCLA helped me connect with other people trying to find film work in Los Angeles. It was an amazing experience, I was exposed to silent films, American studio films and films from other countries. And I started working on many outside student projects always for free! I learned how to light a scene, operate camera, hook up electrical cables to a power box, do make-up, record sound – everything.

What sparked your interest in Cinematography / Special effects?

Watching movies as a kid, I was always thrilled by the photography combined with great locations and action. I liked art, magic and puppets, so clever effects involving trick photography, miniatures, stunts and stop motion fascinated me.

In your youth, which movie impressed you most?

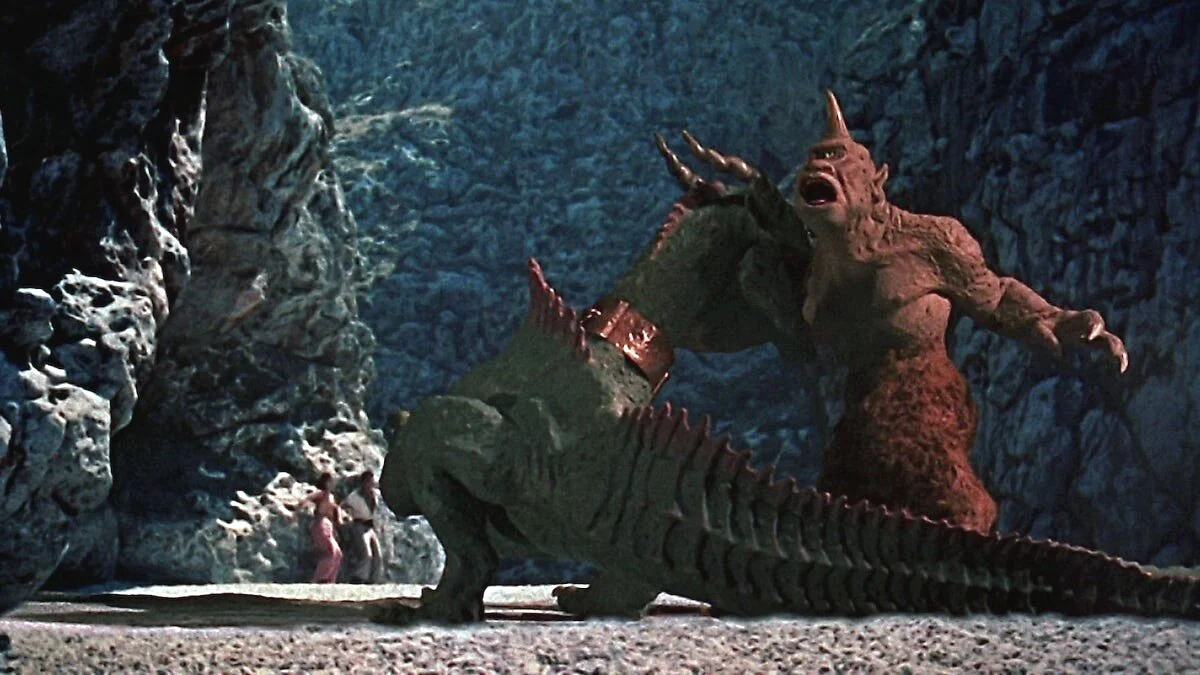

The 7th Voyage of Sinbad simply amazed me! I loved sci-fi and monster movies (anything with Boris Karloff in it)! But so often the creature or the miniature or the effect was on screen for only a moment intercut with many long reaction shots of the actors. The 7th Voyage of Sinbad was different. It was the first movie I'd ever seen that didn't cut away, the shot stayed on the cyclops or the dragon or it stayed on the effect for many seconds. That was fantastic, and I wondered why more movies weren't made that way?

The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, Nathan Juran (1958)

What was your first film ever of your career?

In high school, I was running for office. Usually, you would give a speech or put on a skit. But I decided to make a short film on 8mm. When I showed the film all the students went wild, it was so different, it had a lot of comedy and they loved it. Nevertheless, I didn't win! However, people to this day remember the screening of that movie at my old high school.

What was your first professional film instead?

I was working as a freelance cinematographer and was invited to a warehouse in Van Nuys (LA) to visit a friend of mine from UCLA. He was working on a sci-fi film there. It turned out to be Star Wars although they didn’t have a name yet. I was deeply impressed by the motion control track camera they were using (they named it the Dykstra-flex). It could shoot repeated passes at different exposures and camera speeds of the miniature spaceships. Of course, I wanted to work on this right away. But there were no more jobs. That’s also where I met Dennis Muren who recommended a couple of other movies that were just beginning production. One was Star Trek: The motion picture, the effects were being done by Bob Able. So, I went for an interview, got the job, worked on the film for over a year, and got into the Cinematographer’s Union. I shot most of the Enterprise shots, including when it is in the dry dock. Eventually, Doug Trumbull took over the visual effects from Bob Able, and I worked for him. Doug was basically an artist and painter, and he would produce a piece of artwork and hand it to me and Hoyt Yeatman to try to do it photographically. Every day was constant experimentation. I learned so much during that production and I’m proud of what we accomplished.

Star Trek: The motion picture, Robert Wise (1979)

In the collective imagination, George Lucas and Steven Spielberg are considered the directors-fathers of special effects. You worked with both of them: why were they so innovative and visionary?

I think George and Steven were the first of very few filmmakers who felt comfortable working with visual effects when many other filmmakers were not. They both wisely spent pre-production time with the Art Department designing the look of the film ‒ that became the visual blueprint. In the beginning years at ILM, the only movies we worked on were for George or Steven or some of their close friends who ventured into “the unknown”. After all, they were giving us money to create visual effects shots, always with a lot of trust that the shots would look good! I think the VFX business grew only when writers started writing screenplays containing FX shots, and directors and studios realized the incredible new stories that were only possible using Visual Effects.

In the context of film and television production, a visual effects supervisor is responsible for achieving the creative aims of the director or producers through the use of visual effects. What do you like most about your profession?

Working in visual effects, we are first in and last out. By that I mean our work starts with the director and his team at the very beginning, we get the script, break it down, estimate how many effect shots there are and approximate cost. I work directly with the director through pre-production, production ‒ that's when we shoot the movie ‒ and all the way through post-production. That is when our shot production would begin: we create and put in things that cannot be photographed during production. Quite often our job is not finished until a month before the movie is released. I work on most movies for about 1 1/2 years.

What can you tell me about the transition to digital from photochemical, recalling the days when VFX were done in-camera and assembled via an optical printer?

In the early 80s we were dabbling in digital creation of image, computer graphics as we know it now. I did one of the first CG shots in a motion picture. It was the Genesis effect in Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan. All the FX crews were trying things. Early on a CG model really didn’t look as good as a photographed model. But once Jurassic Park came out, every director and studio wanted us to do computer graphics effects, even if it cost more! We thought the transition from photochemical to CG would take five years. We were so wrong, it took six months!

Jurassic Park, Steven Spielberg (1993)

You have worked in many films with director Robert Zemeckis, such as the legendary Back to the Future trilogy: what can you tell me about your collaboration and those movies?

Ken Ralston was the lead supervisor and I was the associate supervisor when we worked with Bob. Those films were really fun and so creative. Ken worked on the design of shots, I would work on how we would do them. I helped set up the train crash in Back to the Future 3, helped create several solutions for flying actors on Hoverboards for Back to the Future 2, and worked out the methodology for shots in Roger Rabbit (how does a cartoon character hold a real gun?). My team built the Panther Dolly, the very first motion control blimped vistavision camera system that could repeat any movie created on a 40-foot track. We used it extensively for all the splits (a shot where Michael Fox played 2 or 3 characters in the same frame) in Back to the Future 2.

Back to the Future 3 ‘s set, Robert Zemeckis (1990)

In Wolf (1994) directed by Mike Nichols, the cinematographer is the Italian Giuseppe Rotunno AIC-ASC. Which Italian cinematographers, past and present, do you most admire?

Of course, working with Giuseppe Rotunno was an extreme pleasure. He was a quiet gentleman with an incredible eye. He literally sculpted with the light on the set. Working with him and Mike Nichols was an honour. But the first time I was really affected by cinematography was The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. It was shot by Tonino Delli Colli in ways I had never seen. He used long lenses focused in tight close-ups of sweaty faces against out of focus backgrounds. The shine on the faces showed it was hot! And the faces were often Italian or Spanish, and completely unlike anything in American films. Then of course there's Storaro, who is a genius with colour. And Dante Spinotti is amazing at shooting action combined with drama.

Wolf, Mike Nichols, cinematography Giuseppe Rotunno (1994)

With Cocoon ‒ a 1985 American science-fiction comedy-drama film ‒ directed by Ron Howard, you won the Oscar Award. Five more nominations will follow. What do you remember of that film and the prestigious conquest of the statuette?

Ron Howard was always so appreciative of ideas and solutions that we came up with to create his film. Part of the joy of working on that movie was getting to know all the actors, each of them gifted in their own right. I always say an actor really help sell a good effect shot. So whenever Hume Cronyn, Jessica Tandy, Wilford Brimley or Don Ameche was looking at the alien or at the mother ship, you believed it! The whole process was a very pleasurable experience.

Scott Farrar on the set of Cocoon

You have an incredible resume, your films are truly innovative, especially in terms of effects ‒ Star Trek: The motion picture (1979), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), Jurassic Park (1993), Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace (1999), the Transformers film series – especially in recent years computer-generated imagery, or CGI, has changed almost every aspect of special effects. What can you tell me about it?

I think computer graphics allows us to do better work. All visual effects shots are difficult to create. Even now one shot may take weeks or months. But with CG you can now accomplish extremely realistic or fantasy imagery, move with amazing and nearly impossible camera movement, use wonderful animation and do lighting tricks that cannot be done physically. It's true that we're only limited by our imagination and by good ideas!

Cocoon, Ron Howard (1985)

Is there a sequence in your career made by you that you remember with greater pleasure?

I still really like the fight on the freeway between Bonecrusher and Optimist Prime in Transformers 1. It's very cool!

Transformers 1, Michael Bay (2007)

What’s the last film you worked on?

My last film at Ilm, just before I retired, was A Quiet Place. It was a very successful motion picture, I got 98% with rotten tomatoes! So I was asked to help with A Quiet Place 2, which I agreed to work on. I think it is more suspenseful than the first one. We had the Premiere in New York on March 7, 2020, and flew home to California. And that was the week when the entire country and most of the world shut down because of COVID 19! So, Paramount has been waiting since then to release the picture when theatres will be open again! And seeing it is truly the only way to experience that film. So, that was my last film, and no one has seen it yet!

What will the new special visual effects be in the future?

As I mentioned before, visual effects work is still very difficult, laborious and time-consuming. I think we will continue to make the software better and the interface better so that the work becomes much, much easier for the artists in our industry.

Discover our English books on light and cinematography.

Discover our interviews with directors and cinematographers.

Subscribe our newsletter to know about next releases.

The Great Beauty: Told by Director of Photography Luca Bigazzi

paperback and ebook

Active Light: Issues of Light in Contemporary Theatre

paperback and ebook

On Suspiria and Beyond: A Conversation with Cinematographer Luciano Tovoli

paperback and ebook