Lucille Carra was born in Manhattan, New York City. She is an American documentary film director, producer, and writer. She holds a BFA in Film Production and an MA in Cinema Studies from New York University's Tisch School of the Arts. Carra has worked in the distribution and archiving of international films, including the collections of several master Japanese filmmakers. Through her company, Travelfilm, she has produced, directed and written critically acclaimed cultural documentaries on an international scale as The Inland Sea, Dvorak and America, The Last Wright.

What can you tell us about your Italian origins?

My father came to New York from Reggio Calabria when he was five years old; my mother was a first generation American, whose parents came from Catania, Sicily. My mother’s mother came over to join my grandfather. I grew up fascinated by the idea that my grandmother came over to New York on a ship at the age of nineteen with a baby, all by herself.

Which Italian directors and films did you love most?

I grew up very lucky, because we fortunately had access to all the classic Neo-realism films. I’ll explain: In the early 1960s, with the development of television, and with so many Italians in New York, a local television station came up with the idea to show Italian movies on Saturday night, sponsored by Medaglia d’Oro Espresso. An enterprising technician came up with a way to subtitle the prints for broadcast, so we were able to see movies in Italian, which opened up a world to us, different from our beloved Hollywood fare. Ladri di biciclette, La strada, Roma, città aperta, and La dolce vita were strange kind of Italian fairy tales we watched countless times as children. In addition to the essentials of Fellini, Rossellini, and De Sica, in our household Pietro Germi, with Divorzio all’italiana and Sedotta e abbandonata were in a class by themselves. The Sicilian language sounded very familiar and the satire was sublime. In a lifetime of movie viewing, those were the only two films that directly related to my heritage. I feel very strongly that all ethnic groups in the United States need representation on screen. Later on, I also remember the impact of Lina Wertmüller’s Pasqualino Settebellezze because there is comedy along with social commentary. Of course, I loved all Italian cinema, and studied it as much as possible. The latest Fellini, Pasolini, De Sica, and Rosi were all events and essential viewing. Great cinematography is something I always associate with Italian films. On the Beach made a huge impression on me because the footage of Ava Gardner was shot in the open air and she looked different from her other films. My parents noticed the cinematographer was Italian! [Giuseppe Rotunno]. So, at a very early age, I made the connection between beautiful cinematography and Italian cinema. Of course, Giuseppe Rotunno was the connective tissue between so many great Italian and American films. Images that mean more to them than mere storytelling is something I associate with Italian cinema. I say the images are “greater than the sum of their parts.”

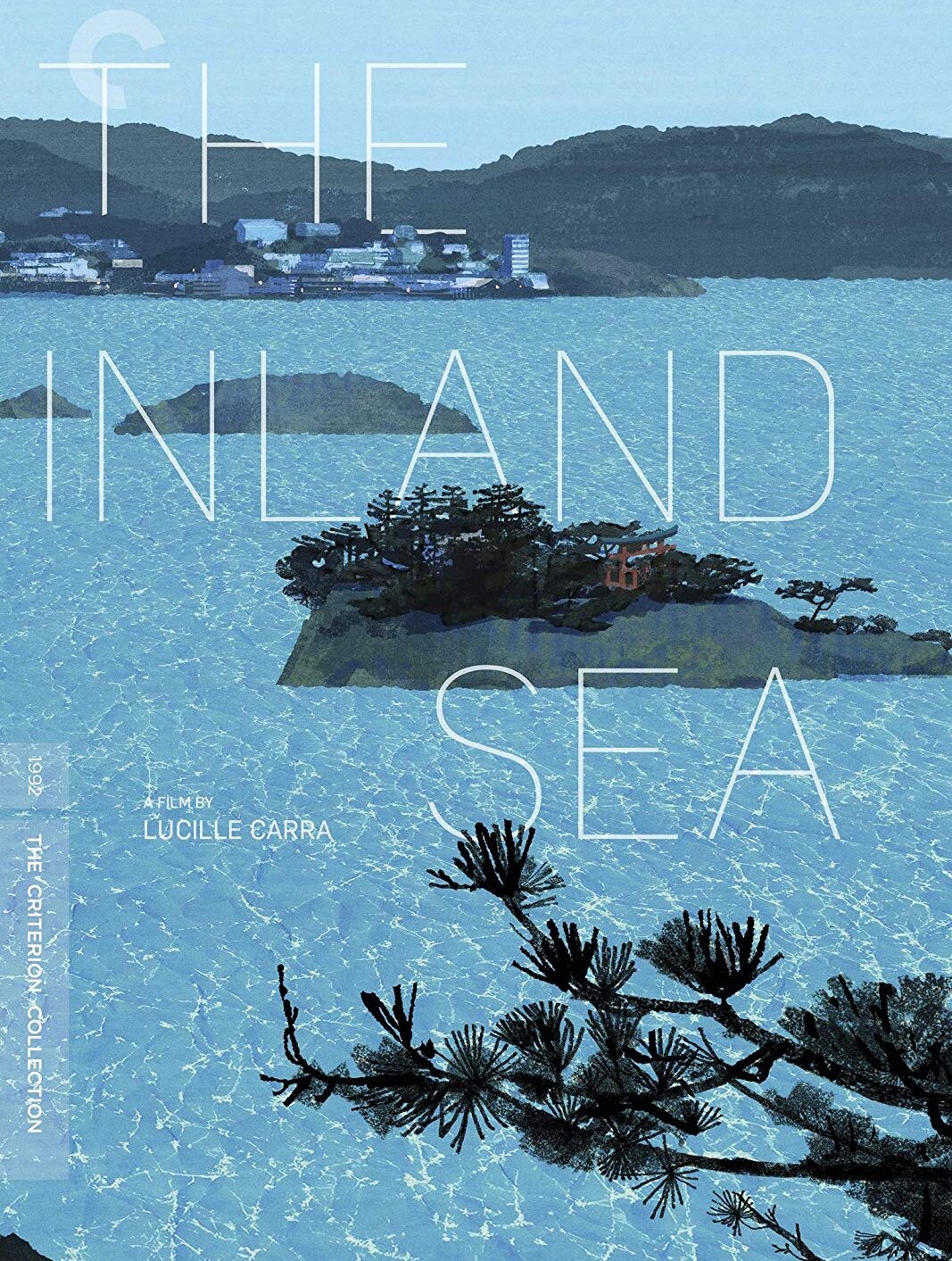

Lucille Carra’s documentary posters

You had attended film school at New York University, where you’d studied under Martin Scorsese and Len Lye, and, thanks to professor William K. Everson, been struck by the poetic use of non sync sound in Humphrey Jennings and Stewart McAllister’s 1942 film Listen to Britain. Can you tell us more about it?

I always wanted to take a Everson class because he would show pirated films he collected that were not allowed to be shown (the FBI was after him at one point), followed by the “legal” film we would study for the class. In graduate school I took his “History of British Cinema” course, which I assumed was Hitchcock …and then everything else. When I saw the World War Two era propaganda documentaries, I was very moved at how you can use sound and image poetically. At the time, cinema verite was very big and of course, and I would see groundbreaking films like Salesman or Grey Gardens. I knew it wasn’t in my character to follow a Bible salesman around and try to sculpt a story. When I decided to make The Inland Sea, I was inspired by the idea that you could sculpt the film beforehand, with a narration by Donald Richie. This freed me, and Hiro Narita, my cinematographer, into not being reliant on the literal representation. Of course, we did shoot synchronous, live sound as we were shooting, but, in The Inland Sea, Donald Richie and all the interview subjects have been filmed in voice-over to create a poetic overlay.

You then worked for Toho International in New York, where you were immersed in Japanese culture and film, is it correct?

I never intended to work for a Japanese film company; my goal was to work in the archives or at a European film office in New York. But I enjoyed working at Toho because I was exposed to all aspects of foreign film distribution, as well as Broadway theatre, as we acquired the rights to current musicals for Japan. I met a lot of theatre producers, directors, set designers and composers. They were always trying to raise money. The Broadway district was very rundown and dangerous in those days, with the porn district sharing space with the legitimate Broadway district. I was in charge of a library of over 200 films, including Godzilla and the films of Kurosawa, and I would book prints for repertory cinemas and colleges. I met all of the big Japanese directors, and saw how they conducted themselves at screenings, and how they protected their work. Kurosawa knew everything about where his films were projected in the U.S., the print condition, the aspect ratio, the film storage. He showed us how you have to fight for your work, and that no detail is too small.

Lucille Carra with director Masahiro Shinoda

So you founded the Travelfilm Company for the production and distribution of documentary films after having worked in international film distribution?

I have been in the foreign distribution business since college, so when I began to make my own films, I had the contacts to sell the documentaries. I found it a great deal of fun, and the contacts were warm and personal. I could go to a film festival, say, in Australia, and meet distributors and television networks. We have a very nice relationship with Ronin Films there, for example.

Your first work as director is the film-documentary The Inland Sea (1991) based on the travel memoir by Donald Richie. Twenty years earlier in 1991 Richie had published his book – a travel classic – titled The Inland Sea; Richie wrote about the Japanese people, the culture of Japan, and especially Japanese cinema, including his volume on Akira Kurosawa. Also wrote the English subtitles for Akira Kurosawa's films Throne of Blood (1957), Red Beard (1965), Kagemusha (1980) and Dreams (1990). Your film (narrated by Richie himself) won the Best Documentary Award at the Hawaii International Film Festival and the Earthwatch Film Award. It screened at over forty film festivals, including the Sundance Film Festival. What can you tell us about this choice? Were you very interested in Japanese culture?

Lucille Carra with Donald Richie

I had been looking for a project, and some colleagues suggested the book, The Inland Sea. I loved the book because I was very drawn to rural Japan, and I admired Donald’s writing style. At the time we made the film, Japan was the number one economic power in the world, and the image of “high-tech Tokyo” prevailed. I personally knew of a warmer side, so I wanted to present that. I also personally felt what it was like to be a foreigner in Japan and to relate to the country and people as an outsider. An interesting draw to the book was that Donald told me he was inspired by a conversational travel book, Old Calabria, by Norman Douglas, written in 1915. The Inland Sea region and the Douglas book reminded me of the nascent memories of Calabria my father had relayed to us. In fact, I threw in a quote from the book and constructed a little scene, as a nod to my father. Donald talks about Japanese people as sea people and their old warmth was “more a Mediterranean than an Asian characteristic.”

Did you already know Richie or Did you already know Richie or did you meet him for your film?

That’s an interesting question, because I knew every Japanese film and theatre person coming into New York from our office, but I never really crossed paths with Donald Richie. I was involved directly with Japan, so I didn’t need an emissary, I guess Donald saw no need to go through our office, because he had his own direct connections. Of course, I had read and reread all of his books on Japanese cinema and they were necessary tools in distributing the classics in our collection.

Just as the book, does your film contain at times a nostalgia for a lost way of life?

Yes, I wanted to make a poetic essay that combined the present day shooting, with a sense of the past (as Donald had written the book thirty years before) but also with a sense of timelessness. In that way, and the polished cinematography and music, make it evergreen.

Donald Richie

For the cinematography you have chosen the well-known cinematographer Hiro Narita ASC. What can you tell us about your collaboration?

I had recently seen Hiro’s film, Never Cry Wolf, a Disney narrative film which has magnificent animal footage, shot in Alaska and Canada. I was very happy that Hiro was enthusiastic about The Inland Sea, because he could do his own camerawork, with his own camera and lenses. And I wanted his input, as well, since he was from Japan. We had a shooting script, and it was very well planned, down to the logistics of carrying the negative back to Tokyo at Imagica Labs every few days. I think the key with working with a cinematographer is letting him/her do their own thing, and once your basic ideas are established, trust them. I was most interested in natural light in the shoot.

The original score was composed by Toru Takemitsu, a well-known Japanese composer who wrote the music for Empire of Passion (1978) directed by Nagisa Ōshima, Ran (1985) directed by Akira Kurosawa, Rising Sun (1993) directed by Philip Kaufman. What can you tell us about him?

Takemitsu was a friend of Donald and was very kind to us in creating a score with a combination of Eastern and Western instruments. We had a script and a tape of the film ready for him, and we wanted music in key spots. It was a lovely collaboration.

The Inland Sea, cinematographer Hiro Narita

A wonderful edition (Blu-ray/Dvd) has been released by the Criterion Collection. Restored 4K digital transfer, supervised by cinematographer Hiro Narita and approved by you, in the edition are therefore present a new interview with you, a new conversation between filmmaker Paul Schrader and cultural critic Ian Buruma on author Donald Richie and interview with Richie himself from 1991. What can you tell us about it?

I’m very happy to say that all my films have been in continuous distribution since they were released. I have had a very good relationship with Criterion/Janus films since my Toho days. The Inland Sea had been initially distributed by Voyager (Criterion) Laserdisc and Janus Films, so we had been through various remasterings. The film was shot on regular 16mm with Eastman Color Print 7384 and some TRI-X for black and white; it was then blown up to 35mm at DuArt Labs in New York. Hiro made it safe for 1:33 and 1:66 aspect ratios. For all of our Criterion work, we went to the 35mm inter-positive and optical tracks. Criterion really does a complete job. When we were making the film, I decided to produce an addendum in the form of an interview with Donald, shot by Hiro. This small film is also in the Criterion package.

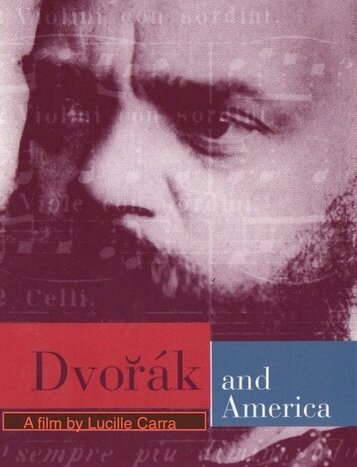

Dvořák and America (2000) was the first U.S./Czech Television documentary co-production. It is the first film about the years the composer Antonín Dvořák spent in the United States as the teaching at the National Conservatory of Music of New York. What is the reason for your interest in this great musician?

Dvorak and America is an example of a film I wanted to make that was pure inspiration. I live near the brownstone where Dvorak wrote the Symphony from The New World (Symphony No. 9 in E Minor.) One day in The Inland Sea, our van was stuck in the mud on a hill, and we suddenly heard chimes playing the “Going Home” theme (Japan has a lot of chimes on train stations, crosswalks, etc.) I thought of the universality of the music, and I started researching. I liked that Dvorak lived in my neighborhood and made daily walks down Broadway to my street to drink beer at the cafe. It was a lot of work to properly research the film, because when we started, the Iron Curtain had just recently fallen. The archives opened up more and more, each year. We were the first U.S. – Czech Television documentary co-production. I also was able to make contact with the “Czech Film Office” which was a holdover of the Communist era. It was fascinating to meet filmmakers in a country we had been prohibited from visiting for the previous 40 years or so. We processed some film there and also at Hungarian FilmLab in Budapest!

Antonín Dvořák

Do you also explore Antonin Dvorak's relationship with his African American students in New York in this work?

Dvorak’s relationship to his African-American students had never been told on screen before and is still little known. Harry T. Burleigh, America’s greatest Art Song composer, and Will Marion Cook, who composed the first Broadway musical, were among his classical students (although Burleigh was his copyist and an informal student). There was so much musical action around New York City in the late 1800s and we don’t know much about it. Educational television stations in the U.S. do not want to fund films about periods before the advent of motion pictures. I hope we can rectify this and make more films about these earlier periods, even if footage doesn’t exist.

The cinematographers are Antonín Chundela, Allen Moore and also Narita (just New York and the Midwest). Can you explain the choice of three different cinematographers?

I was very eager to work with Hiro again, and he added so much to our shots of Manhattan and Iowa. We shot in Minnesota, as well. His work is really beautiful without being sentimental. Dvorak was a profound lover of nature, and would take long walks at 5:00 am. I wanted to get that quality through the cinematography. I wanted to work with Allen Moore with the interviews because he did signature work with the American documentarian Ken Burns. Since our interviews took place at different times and locations, I worked around his schedule. Hiro wasn’t available for the Czech Republic shoots, so Antonin Chundela, who was graduating from FAMU, the famed Czech film school, was recommended. He is an example of the talent and craftsmanship of FAMU, and he studied Hiro’s and Allen’s work to give the film its uniform look. I learned a lot about FAMU and Eastern European cinematography while I was in Prague. In the 1990s, you could still justify shooting a documentary on film, so we even shot the archival stills on film, and did not scan them. We really need to preserve older independent documentaries that were shot on film and have very interesting visuals and audio work in their outtakes.

The Last Wright: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Park Inn Hotel (2008), produced and written with Garry McGee, is the only project in any media about the last standing hotel designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, The Park Inn, located in Iowa. The film won the Grand Prize as Best Documentary at the Iowa Motion Picture Association and was nominated for an EMMY Award for Best Writing for Documentary. Wright's works have appeared or inspired the environments of films such as Michael Curtiz's Female (1933), Edgar G. Ulmer's The Black Cat (1934), Alfred Hitchcock‘s North by Northwest (1959), George Lucas’s THX-1138 (1971), Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982). The director Nicholas Ray (Rebel without a Cause) studied with him and in addition, music also celebrated him when in 1970 Simon & Garfunkel dedicated to him entitled So Long, Frank Lloyd Wright. I guess you're an admirer of Wright's work too?

The Park Inn Hotel by Frank Lloyd Wright

That is a great list of Wright on Film. I always liked that Nicholas Ray studied with him. I love Wright’s work, and I was fascinated by him initially because of North By Northwest, which, we know, isn’t technically a Wright building!

Did you conduct your work through rare archival footage, period music and a comparative look at famous Wright structures?

Instead of making a biopic of this remote hotel, I decided to do a comparative study to show its relationship to other Wright structures. Very early in my research, I explored the relationship between this little hotel and Wright’s iconic Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. The Japan connections were very strong, and Wright was profoundly influenced by Japanese aesthetic and architecture. We shot on 16mm film, and I believe it’s the last time Wright’s Wisconsin home, Taliesin, was shot on film; we shot the interviews on DVCam, and Antonin Chundela gave the interviews a lovely film-like look. It actually worked better than 4K would have worked.

Which is your favorite work?

My favorite work is Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois. Wright’s mother was of the Unitarian faith and you really feel a spiritual pull in this space. I also love the restored Robie House in Chicago, which has a perfect blend of indoor, outdoor, ornamentation, space and light. Visiting this house, you feel an “out of body” experience - hallucinogenic, really, especially with the stained glass window placements against the outdoor light. A very interesting aspect of Wright’s work are the acoustics. You could give a great piano recital in any of his buildings.

Has Frank Lloyd Wright's historic Park Inn Hotel been restored today?

Yes it is, but it is a commercial property, which can only be as authentic as the owners allow. I’ve heard it’s okay.

In 2007, researching material for a film on pianist Glenn Gould, you found the long-thought lost U.S. television program written and performed by the performer, The Return of the Wizard (1968). Glenn Gould, Recording Artist is the first film to explore the intersection between Gould's classical musical recordings for Columbia Records and his experimental radio art in Canada, is it exact?

Glenn Gould and producer Howard Scott. Photo: Plaut Collection, Yale University

Growing up, like many youngsters, I was fascinated by Columbia Records, and Columbia Masterworks, their classical label. Going to NYU in Greenwich Village, we would wonder who was recording at the Columbia Studio at East 20th Street that day. The studio was located three blocks up from where Dvorak wrote The New World Symphony, so once again I was intrigued that a source of great music was in my neighborhood. I was interested in Glenn Gould because he quit live performance and was obsessed with editing his performances and with making his acoustics in line with recording aesthetics and not, as was the custom, replicating a live performance, with an overhead mic. When you think about it, it makes perfect sense. Gould also began making radio documentaries about Canadian subjects for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, which were also edited in the extreme. These experimental works are intricately constructed. He also wrote extensively about his editing theories. If Gould had made experimental films instead of audio, he would be much more well known in this field. We interviewed Gould’s record producers at Columbia Masterworks and his editors at the CBC. It’s wonderful material that brings to life a period in analogue recording that few remember. We found a lot of forgotten material, and talked about Gould as an editing enthusiast, which I think is very interesting for filmmakers. In the annals of Glenn Gould, a program he made for Public Television in New York, called The Return of the Wizard was considered lost. I found it, and realized that a perfect two inches master was located at the Library of Congress. I went to Washington, DC, checked it out, arranged to have this duplicated, and it was great fun to present it in Montreal, New York, and Munich. There was always a sellout crowd. Interestingly, David Oppenheimer, who had discovered Gould and signed him with Columbia, produced this program, and the following year, he became Dean at New York University’s School of the Arts, where I eventually studied. Kirk Browning was a very innovative and prolific television director who directed this program; some of Browning’s most beautiful live transmissions are early Metropolitan Opera broadcasts with Luciano Pavarotti, Renata Scotto and other greats of the 1970s. We wanted to publish a pristine DVD of “Return of the Wizard,” but there were a lot of squabbles. It deserves to have a decent DVD release.

Glenn Gould

At what point is the processing?

I had put the project on hold for a variety of reasons, but it is essentially finished and we should be getting it out.

In conclusion. In addition to being a writer and director, you are also, as we have mentioned, a producer and distributor. In your opinion, what will the future of the film industry look like when this dramatic pandemic ends?

I started in foreign film distribution in the United States, and then moved on to a very niche market for independent documentaries. As a film lover and film goer, my instinct tells me that when the pandemic is over, and if we return to our previous lifestyle, I predict that we will recover our former habits. Anecdotally, I see that people are bursting to get out of the house. I worked in Broadway theatre in the 1980s, when it was said that live theatre was dead, but the business came back tremendously. I think young people especially, will want to go out and go to the movies. I do also think that there is no turning back with streaming new films on your flat screen TV and paying for them upon release. It will be a hybrid experience. We will choose to see a film on the big screen or at home. I also think Netflix and HBO should offer their “binge-worthy” programs on the big screen as special events for those of us who want that experience. I saw two old Game of Throne episodes on IMAX and the theatre was packed. Sometimes, you just want to be with people. IMAX could be great to bring in theatre, opera, concerts, and sports. It’s up to the exhibitors to provide good business models so that we have a comfortable experience.

Discover our interview with directors and cinematographers.

Discover our books and subscribe to our newsletter to be informed about new releases and events.